A few weeks ago I flew with Virgin to South Africa for work. Flights to South Africa from the UK are only ever overnight which for me is a shame, because I detest trying to sleep on an overnight flight. For anyone like me who wants to get on with other things whilst they fly, Virgin provide in flight WiFi – at a cost of £4.99 a device. I learned you had to pay only once the captive portal page kicked in. But seeing as I was already on the WiFi, I decided to do some poking around. Here’s what I found

An important foreword:

<legal> Hacking a system without explicit authorisation by the organisation or individual who owns the system is illegal pretty much everywhere and in the UK it falls under the Computer Misuse Act of 1990. Not only that, it’s almost certainly against Virgin’s in flight WiFi Acceptable use policy. What I describe in this article is not hacking of any kind. Whereas in a capture the flag competition or penetration test I might use probing tools, enumeration techniques, and vulnerability scanners, here I was simply using firefox’s network monitor to see what the browser would be loading under normal use anyway, and calling that. </legal>

Not so free WiFi

Initially I just wanted to get on the WiFi for free. Although you have to pay £4.99 for anything usable Virgin offer a free chunk of 250mb (I think) if you complete a survey, however it was suffering from some interesting technical issues:

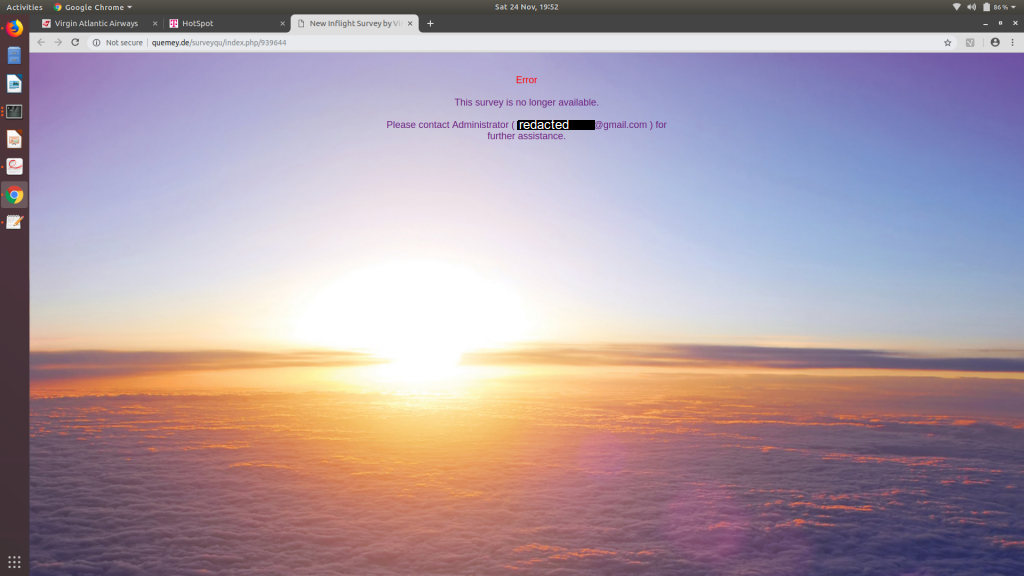

If you can’t read what the tiny text says, the message reads:

Error

This survey is no longer available.

Please contact Administrator ( <gmail email address> ) for further assistance.

This is what I was greeted with when I pressed the ‘do questionnaire’ button. It’s interesting to me for a few reasons:

- It contains what looks like a personal gmail address for support enquiries.

- The domain (quemey.de) appears to be live on the internet, suggesting that even before I’ve purchased WiFi you can access the internet on certain whitelisted sites. (You can see the T-mobile hotspot page open in another tab). Most captive portals serve everything locally and only grant internet access after you’ve signed in and/or paid.

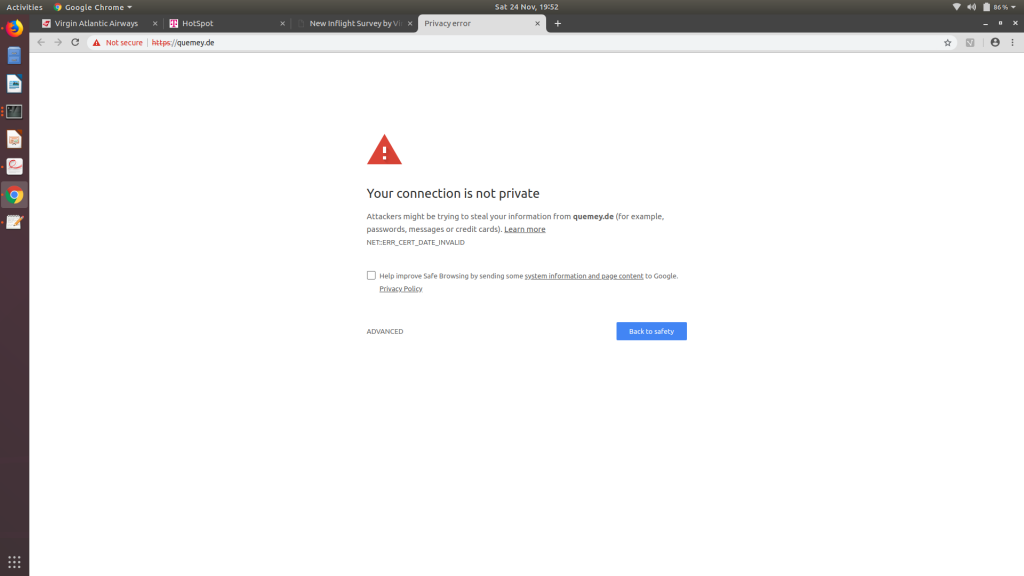

I removed the context path from the URL and pointed my web browser to the root (https://quemey.de) and was greeting with an expired certificate:

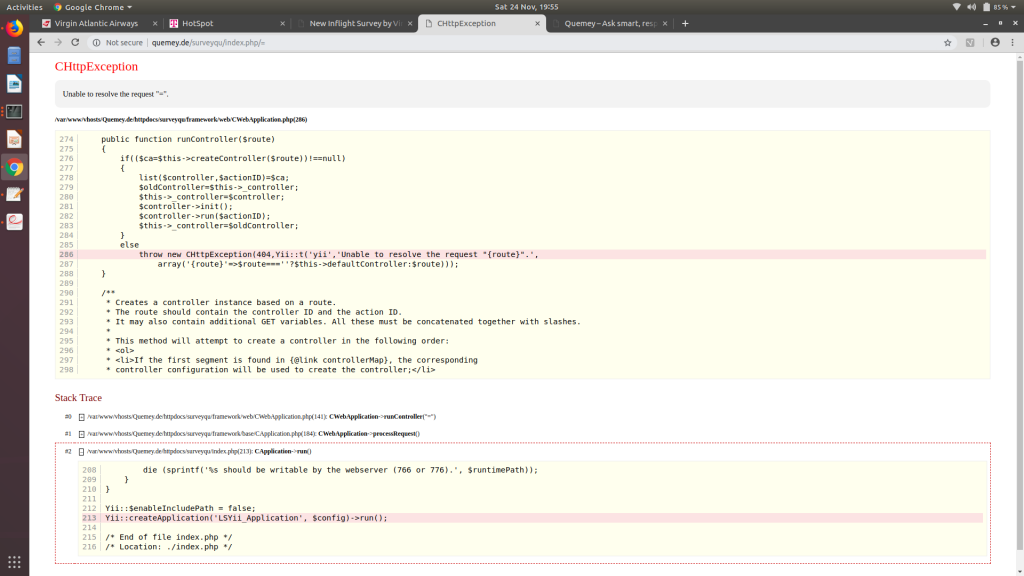

The certificate had expired in August, and it was currently the end of November. Clearly this site was having some trouble. This was further reinforced when I was deleting the path from the previous URL and I accidentally hit = instead of the delete key, taking me to https://quemey.de/surveyqu/index.php/=, and the web server promptly spat a bunch of the server code at me:

Live flight data

At this point I decided to leave the quemey.de domain alone, it was clearly having some issues and it’s best to avoid the situation if it starts to feel like you could actually break something.

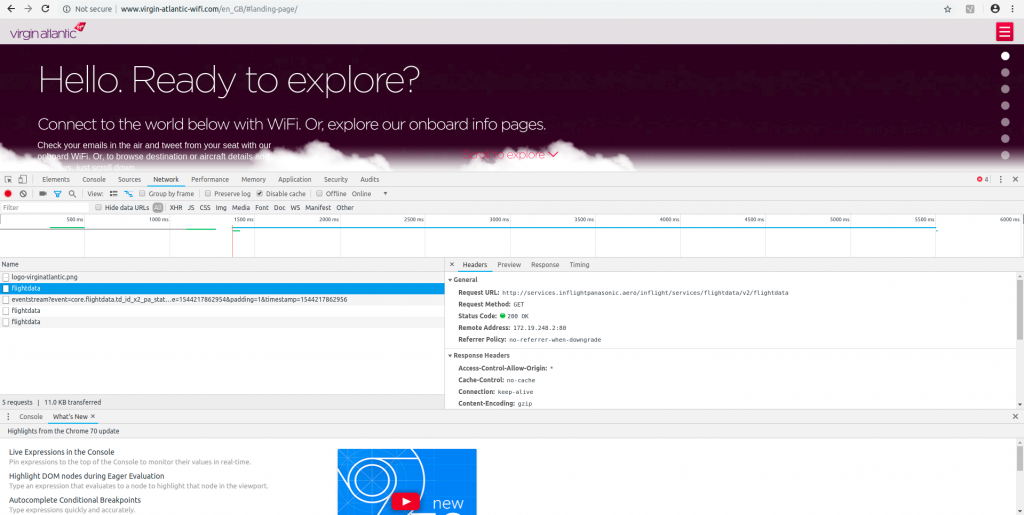

Resigned to the idea that I wasn’t getting my free in-flight WiFi for doing a questionnaire I moved on to other things, but when I later went to close the captive portal tab I noticed another interesting URL in the network monitor:

The url was

http://services.inflightpanasonic.aero/inflight/services/flightdata/v2/flightdata

this caught my attention because the .aero top level domain is restricted for registration – you have to work in the aerospace industry to get one. I’d never seen the .aero TLD used before, and when I hit the endpoint I was pleasantly surprised to see a bunch of JSON-formatted data returned about the flight:

{

"td_id_decompression":"0",

"td_id_weight_on_wheels":"0",

"td_id_all_doors_closed":"1",

"td_id_x2_pa_state":"0",

"td_id_fltdata_ground_speed":"0471",

"td_id_fltdata_time_to_destination":"0547",

"td_id_fltdata_wind_speed":"0034",

"td_id_fltdata_mach":"0854",

"td_id_fltdata_true_heading":"0169",

"td_id_fltdata_gmt":"2042",

"td_id_fltdata_outside_air_temp":"8056",

"td_id_fltdata_head_wind_speed":"",

"td_id_fltdata_date":"00241118",

"td_id_fltdata_distance_to_destination":"00004411",

"td_id_fltdata_altitude":"00035002",

"td_id_fltdata_present_position_latitude":"00041515",

"td_id_fltdata_present_position_longitude":"00002069",

"td_id_fltdata_destination_latitude":"80026082",

"td_id_fltdata_destination_longitude":"00028144",

"td_id_fltdata_destination_id":"FAOR",

"td_id_fltdata_departure_id":"EGLL",

"td_id_fltdata_flight_number":"VIR601 ",

"td_id_fltdata_destination_baggage_id":"JNB",

"td_id_fltdata_departure_baggage_id":"LHR",

"td_id_airframe_tail_number":"G-VNYL",

"td_id_flight_phase":"7",

"td_id_gmt_offset_departure":"00000.00",

"td_id_gmt_offset_destination":"00002.00",

"td_id_route_id":"69",

"td_id_fltdata_time_at_origin":"2042",

"td_id_fltdata_time_at_destination":"2242",

"td_id_fltdata_distance_from_origin":"00000596",

"td_id_fltdata_distance_traveled":"00000591",

"td_id_fltdata_estimated_arrival_time":"0749",

"td_id_fltdata_time_at_takeoff":"002411181923",

"td_id_fltdata_departure_latitude":"00051280",

"td_id_fltdata_departure_longitude":"80000265",

"td_id_pdi_fltdata_departure_iata":"",

"td_id_pdi_fltdata_departure_time_scheduled":"",

"td_id_pdi_fltdata_arrival_iata":"",

"td_id_fltdata_wind_direction":"0230",

"td_id_media_date":"20181124",

"td_id_extv_channel_listing_version":"1094"

}

Awesome.

So naturally the next step was to write a dashboard to parse, group and pretty print this data out. The monitors that each seat has in front of it for watching films etc do display some flight information (which is what I suspect this endpoint is for), but this is a lot more than gets displayed there.

A CORS for Concern

My plan was to use JQuery and bootstrap (which I luckily had local copies of on my laptop) to whip up a dashboard that would display this information, but this is where things get a little technical. The API endpoint I was calling (/inflight/services/flightdata/v2/flightdata) was on the domain services.inflightpanasonic.aero. Whilst I could call this endpoint from my laptop using cURL no problem, it’s not quite so simple when you want to call out from a web page.

Cross-Origin Resource Sharing, or CORS, is the process by which a web server can allow or deny it’s endpoints to be called by another website. This is a fundamental security feature of the web which prevents things like Cross-site scripting (in some cases), as well as people using your endpoints on their website without permission. If I have a site (domainA.com), and I want to call an API on domainB.com from Javascript in the browser (an XMLHttpRequest) I can add a CORS header to the response from serverB.com which contains a site whitelist. E.g.

Access-Control-Allow-Origin: domainA.comThis tells the web browser that if the user is on domainA.com, it is allowed to call endpoints on domainB.com, otherwise it isn’t. The browser will then permit or deny the request as required.

In this scenario I have no control over the remote server and therefore I can’t add the required CORS header to allow me to call the endpoint from my dashboard. There is, however, a workaround. I put together a nodeJS program using a library I had already used before called http-proxy. This would allow my dashboard to call the nodeJS server locally on my laptop, which would in turn call the Panasonic endpoint. When the response from the endpoint came back, the nodeJS server would add the CORS headers and return it to my browser, thereby allowing me to get the data after all. This works because the nodeJS proxy program isn’t a browser, and therefore doesn’t need to honour the CORS headers, present or not.

Node to the rescue

The nodeJS code ended up being only 30 lines long:

var http = require('http'),

httpProxy = require('http-proxy');

var proxy = httpProxy.createProxyServer({

secure: false

});

proxy.on('proxyReq', function(proxyReq, req, res, options) {

console.log("-> " + proxyReq.path);

proxyReq.setHeader('Connection', 'keep-alive');

proxyReq.setHeader('Pragma', 'no-cache');

proxyReq.setHeader('User-Agent', 'Mozilla/5.0 (X11; Linux x86_64) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Ubuntu Chromium/70.0.3538.77 Chrome/70.0.3538.77 Safari/537.36');

proxyReq.setHeader('Accept', 'text/html,application/xhtml+xml,application/xml;q=0.9,image/webp,image/apng,*/*;q=0.8')

});

proxy.on('proxyRes', function(proxyRes, req, res) {

console.log("<- " + proxyRes);

res.setHeader('Access-Control-Allow-Origin', '*');

res.setHeader('Access-Control-Allow-Methods', "GET,POST,PUT,DELETE,HEAD");

});

var server = http.createServer(function(req, res) {

proxy.web(req, res, {

target: "http://services.inflightpanasonic.aero"

});

});

console.log("listening on port 3000")

server.listen(3000);

When run, I can hit my local machine on port 3000 and any path I provide will be passed to services.inflightpanasonic.aero, and the response will have the CORS header attached. So from my dashboard I target

http://127.0.0.1:3000/inflight/services/flightdata/v2/flightdata/

and the node script will call

http://services.inflightpanasonic.aero/inflight/services/flightdata/v2/flightdata

then, on the response, it will add the header

Access-Control-Allow-Origin: *

and now my dashboard won’t encounter any issues. Or so I thought…

Once I tried it, I kept getting the Virgin WiFi login page back instead of the endpoint. At first I thought it was because I wasn’t logged in, but then I remembered I was never logged in at any point. I gave it some thought and noticed that the response was coming from an Nginx server. Nginx is a reverse proxy that differentiates backend destinations by the HOST headers (the address in the web browser). If all my traffic is going to the same server (Nginx), then being proxied to the appropriate backend, Nginx won’t know where I’m trying to go if I don’t provide the host header, and evidently the fallback behavior is to return the initial logon page.

I added the line

proxyReq.setHeader('Host', 'services.inflightpanasonic.aero');

to the “proxy.on(‘proxyReq'” section of the above code, and now that Nginx knew where I was trying to go, I got the api contents back, with the CORS headers too. Nice.

Writing the dashboard

I won’t go into too much detail about how I wrote the dashboard. It uses a mix of a few web technologies and libraries I already had offline copies of on my laptop, notably bootstrap, font awesome, and Jquery.

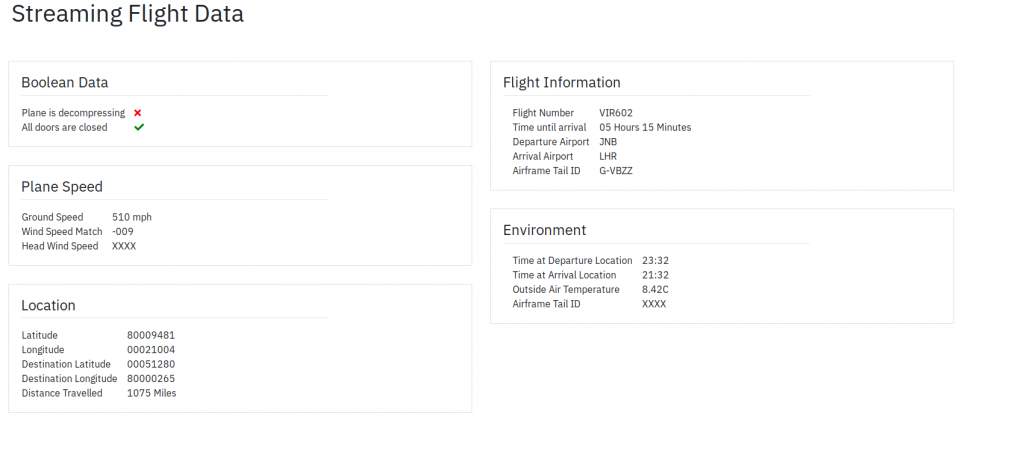

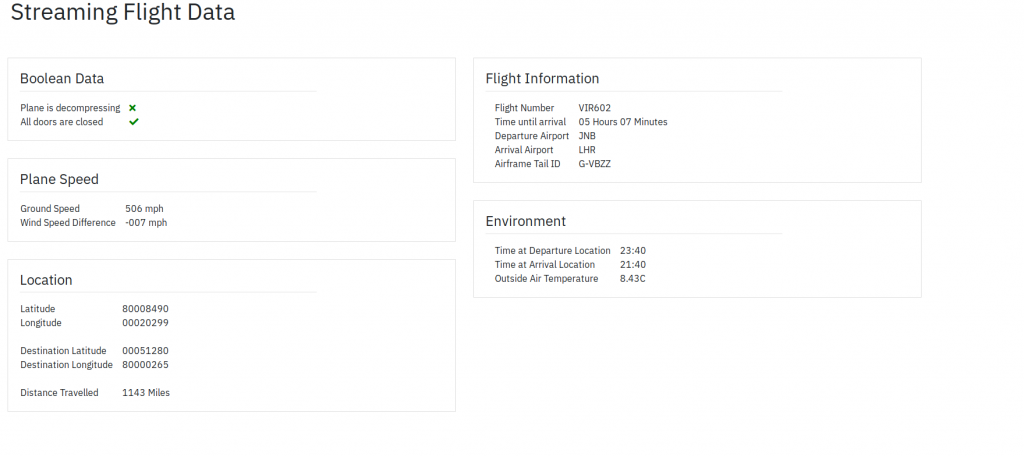

I wrote some Javascript / JQuery code to periodically call the endpoint and parse the data, and the end result was:

Here you can see the information I chose to display. It isn’t everything that the endpoint returns, partly because I wasn’t sure what all of it meant (like td_id_x2_pa_state, maybe whether the public address system is in use?), but we can see some more information that the Vera dashboard built into the headrest of the seat in front doesn’t show, like whether the plane is decompressing or not. Thankfully it wasn’t. I had a function where I pass in a boolean (true or false), and it would return a green tick for true and a red cross for false, however I felt that plane decompressing = no shouldn’t be a bad thing, so I updated the function to optionally accept an invert colours flag. Now I had this:

There were some interesting techniques used to present the data that I had to second guess as I had no documentation to go on. For example, the Latitude and Longitudes would sometimes start with an 8. I assume this is when they should start with a +, so I updated it to do a simple replace operation of the first character. Another example was the temperature, which was returned as 8043. I took the liberty of assuming the 0 was in place of a decimal point, and the API only wanted to return a-z, 0-9. However as the vera dashboard didn’t appear to show outside temperature I couldn’t confirm this was correct. Finally, the Time until arrival appeared to be HH:MM as normal, but sometimes the minutes might be :85, so in the end I decided you had to do a mod 60 on the minutes, and add that to the hours value, and that seemed to make my dashboard’s time remaining line up with the real figure.

Sadly the in flight WiFi is turned off when the plane begins to land, so I didn’t get a chance to see ‘All doors closed’ turn to no, or decompressing turn to yes. But it was an interesting foray into reverse engineering someone else’s works, I’m sure the weird API workarounds are in place for valid reasons, and that somewhere out there they’re all documented. For me, it was an interesting way to kill a couple of hours on the plane. I never did try to do a PUT against the doors closed though….

If you want to view all the code yourself (maybe you’re taking a virgin flight soon), it’s on github here. If you have any improvements, please open a pull request!